A study published in mid-March by Statistics Canada found an increased risk of cybervictimization among Canadian youth and young adults ages 12 to 29.

For the youth under 30 born into the digital age, online learning, remote working, digital services and social media interaction have become an inseparable part of their life with the contribution of the Covid-19 pandemic. Besides the various positive effects of this tech ecosystem on the youth, it also has some negative consequences. Here Statistics Canada‘s research paints a picture of one of these adverse outcomes, cyberbullying.

Johanna Sam, is an Assistant Professor and expert on digital pedagogies at the University of British Colombia. “Cybervictimization means that an individual or group is attacked online. It’s usually a repeated repost of hurtful content intended to inflict harm on somebody,” says Sam.

According to the study, in 2019, one in four teens (25 per cent) between the ages of 12 and 17 reported that they had experienced cyberbullying in the previous year. Threatened or humiliated online or via text messages stood out as the most common form of cyberbullying, at 16 per cent.

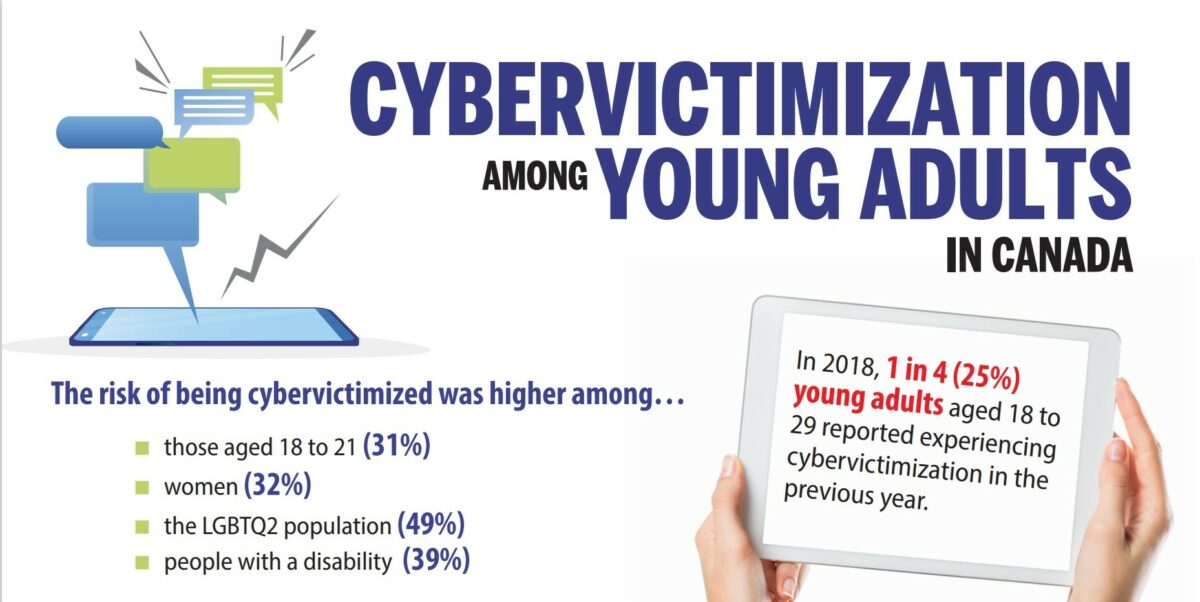

The study also shows some young people are more vulnerable to cyber victimization, including the LGBTQ2 population, people with disabilities, women, and those aged 18 to 21. Accordingly, the LGBTQ2 population leads the way in cyber victimization with 49 per cent, followed by people with disabilities at 39 per cent, women at 32 per cent, and those between 18 and 21 at 31 per cent.

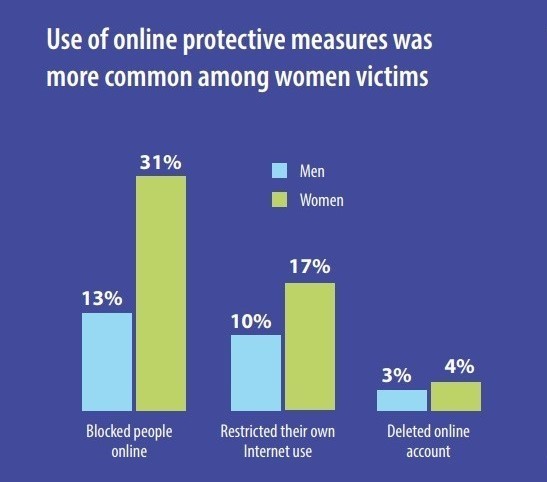

Therefore, online protection measures are more common among women victims than men. While 31 percent of female users prefer to block people compared to negative behaviour, this rate remains 17 per cent for men.

“I sometimes receive emails promising gift cards on behalf of some companies. I just ignore them because I know which ones are fake and which ones are actually legitimate. So I don’t check the email unless it comes towards me,” says Francine Padilla, an Art Fundamentals student at Sheridan College.

“Never trust anything that you cannon verify. For instance, you got an email or a text message; if you see anything suspicious, use common sense. Don’t click anything that you are not expecting to receive,” says Ivan Gonzales, a Cyber Security Expert at Deloitte Canada.

“I always get text messages that I have an e-transfer waiting. Like 50$ click this link to redeem it. And sometimes I think it is real because it might be my friend who might owe me money. But then I check it again, and I don’t think this is real. Because usually my friends send it right away and it wouldn’t be there. I usually report and block the phone number,” says Melody Sang, an Information Systems Security student at Sheridan College.

Looking at the research results, it would be helpful for the more vulnerable groups to be aware of cybervictimization, to be more skeptical of the internet environment and to use verification mechanisms.