Homelessness gets a lot of news coverage during the winter months. Sub-zero temperatures and emergency shelters often turn a concerned eye on an issue that’s ignored for much of the year.

“It’s been consistently on the rise for the last three years,” says Trish Trapani, a manager at a local food bank. She’s talking about the number of homeless clients the food bank serves. Although not a majority, a significant percentage of the people who visit the food bank could be defined as homeless.

“Homeless is not having a permanent residence, whether you’re couch surfing or living in your vehicle,” she says. “We have people that are living at the shelter and then, of course, the people living in the parks.”

Trapani says that there is maybe a slight rise in the number of homeless people in her area during the summer months but that homelessness itself is a consistent problem. The Compass, the southern Mississauga food bank where she works, saw six new homeless clients in just one day last week.

“We’re seeing more and more of it in Southern Mississauga, that’s for sure,” she says. The Compass served between 30 to 40 homeless people in the month of January alone.

Homelessness is also sometimes thought of as an urban issue. Downtrodden people begging on the side of the street are now considered a part of the city landscape. This view, however, is often incomplete. Many people live without a home in smaller suburban communities like Mississauga and Oakville, too.

Downtrodden people begging on the side of the street are now considered a part of the city landscape.

“One of the major challenges for researchers, policymakers as well as advocates is attempting to quantify or count the amount of people that experience homelessness,” says Professor Rory Sommers. Sommers has a PhD in Sociological-Criminology and studies youth homelessness in Canada. He believes accounting for the number of homeless people in smaller communities is more difficult than it is in Toronto or Montreal.

Although the statistics are not as up to date as they perhaps should be, the problem of homelessness can be seen throughout the GTA.

“A lot of people wouldn’t even think there is homelessness in Oakville,” says Justin Brito, an Oakville-based artist and entrepreneur.

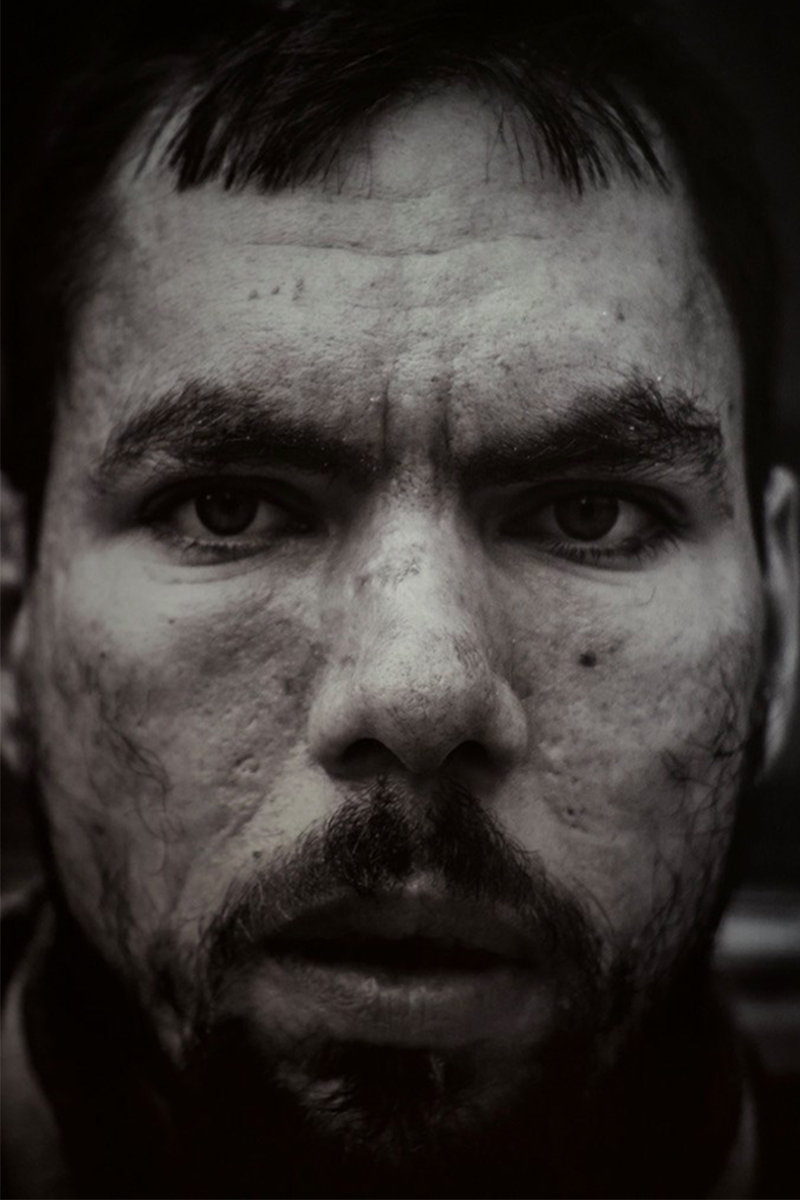

Justin Brito’s work pairs sometimes harrowing portraits of the faces of GTA homeless people with positive quotes and advice. The project aims at rehabilitating the perception of homeless people in the eyes of Canada’s youth.

“I think because it carries such a notoriety with being rich and wealthy. People don’t understand that there are shelters in Oakville. There are a lot of younger children in Oakville that are homeless too,’ says Brito.

Brito was inspired by a meaningful encounter with a homeless man many years ago and has since completed photography projects aimed at drawing attention to the problem. For his 2018 Two Cents for Change project, he took intimate portraits of the faces of downtown Toronto’s homeless people. He also asked his subjects for positive quotes, which he exhibited alongside the portraits. He’s hoping to inspire youth to see these dispossessed people in a more respectful and understanding way.

“Poverty is poverty; homelessness is homelessness,” he says. “People act like there’s really not a sense of urgency behind trying to help. They are just walked by daily.”

“People act like there’s really not a sense of urgency behind trying to help.”

Justin Brito, Oakville-based Artist and Entrepreneur

This lack of urgency can often be seen by the sides of highways in the areas around Sheridan. Car after car slides past lonely and exposed men and women who hold signs, standing on exit-ramp sidewalks.

“It all depends, if people are going to be kind, I guess,” says Tom, a tall thin man panhandling by a Mississauga QEW exit ramp. “Sometimes they’re kinder in the winter,” he says. Sometimes they aren’t.

Do the police ever bother him?

“They try to,” he says. “I’ve gotten a few tickets, around 60 bucks. Make 30 bucks, get a 60-dollar ticket.”

“Make 30 bucks, get a 60-dollar ticket.”

A homeless man named Tom on his interactions with police

Tom mentions he is staying with a friend nearby. He’s never stayed in a shelter and can’t see himself doing it. He knows people who have stayed there and encountered problems.

“They’ll steal the shoes off your feet,” he says, referring to the other residents.

“A lot of people just refuse to stay in shelters because of the circumstances,” says Trish Trapani. “There’s different reasons people find themselves in a homeless situation. It could be mental health issues, coupled with a substance use disorder. Some people’s life just went right, and they went left.”

Whatever the reason, she explains, taking a large number of people with substantial socio-economic disadvantages and putting them all together can lead to “uncomfortable situations.”

Being homeless opens people up to all kinds of risks and health problems.

“The difference between big city and suburbia is that in suburbia it’s more hidden,” says Trapani. “People say, ‘not in my backyard’ or ‘I don’t see it.’”

“But it’s happening, so we need to stop pretending it doesn’t exist,” she says. “It does exist and these people who are homeless are real people. They’re not any different from you or me.”

The most striking moments Justin Brito experienced doing his work were “how thankful a lot of the homeless individuals were.”

“They thanked me for even giving them the opportunity to talk,” he says. “It was shocking to see how you can sense and see the disconnect between your average human being and someone who is going through it.”

The most important thing, he believes, is carrying on a conversation with people who are suffering through homelessness. That means treating them like human beings.

Well written and a helpful artucke in understanding the issue of homelessness .